Of Unicorns and Ivory Towers: Collaborative Career Education in the Higher Education Sector

09/02/2021

Susanne Jones is a careers consultant at the Australian National University, proactive in developing a Career Literacy Framework to discuss career education in a logical and structured way. The framework enables career education to be embedded in courses and to articulate to students, academics and professional staff the core capabilities needed to manage their careers and employability. Susanne was a 2020 recipient of the CDAA Awards for Excellence in Practice for the ACT Division.

Being a career practitioner at Australia’s national university comes pretty close to a dream job for me.

I get to work with young people at a time in their lives when they have the luxury of space to explore who they are, what drives them and where they want to focus their energy on. I love that moment when our conversation hits on their values and passions, I see the spark in their eyes and can help them create the connection between that spark and their future. Their stories – good and bad – are inspiring, and being able to help them clear a few cognitive or emotional roadblocks on their way to their dream career is hugely rewarding.

Being a university career practitioner in a comparatively small team, servicing over 20,000 domestic and international students across all academic disciplines, is at times also hugely frustrating. Many students don’t engage with their careers service until very late in their degree (or not at all), they struggle with the basics of finding and applying for a job, they don’t know how to translate their often very diverse and impressive transferable skills to a job application, let alone a career, and graduate outcome data continually shows that once they do find a job, it is too often not related to their degree much at all.

Expectations of what a career service should and shouldn’t deliver differ vastly between stakeholders, and the cornerstones of our service – 1-1 consultations, workshops and employer engagement events – are near impossible to scale up without significantly increasing the number of staff.

But, as the much-quoted line goes, in every challenge lies an opportunity (variations of this are usually traced back to Albert Einstein so I feel in good company) and when I started at the ANU as a freshly minted and bright-eyed career practitioner in 2019, I felt there was indeed space to try something different.

The career education unicorn

Put simply, the brief for any careers service is to improve the employability of its clients. In a place with potentially over 20,000 clients, the challenge is to reach as many as possible to create a positive and lasting impact.

We all know only too well that the potential positive impact of a 1-1 consultation is huge, but the reach is minimal. On the flipside, maximising reach through large-scale lectures or content-heavy websites that try to cover every aspect of career development tends to have little impact.

What if we could find a way to motivate students to engage with career education on a long-term basis and take charge of their own career development? Or, metaphorically speaking, how can we stop handing out fish to the random few and instead teach everyone to fish?

A capability framework

Most students come to us with one of two questions (often both): “what can I do with my degree?” and “I’m not sure how to write my application / what to say in my interview”. Those two questions sound straightforward, but once unpacked touch on every aspect of career development. You can’t fix what you don’t know and I felt that half the problem was that students were blissfully unaware of the complexity of career development, which limited their thinking about suitable careers. “There’s nothing on Seek” is a classical indicator of not just a real knowledge gap in finding and navigating career information (= skill), but also of a lack of creative thinking about careers and lack of strategies to create work rather than sit back and wait for opportunities (= capability). I felt that students were significantly held back by their insufficient understanding of themselves, the labour market and good career development practice (i.e. reflection, learning and good decision-making), and I wanted to fix it.

In my research, I had come across the term “career literacy” in a paper by Peter McIlveen and Peter Tatham, which really resonated with me as I felt it perfectly captured the hierarchy of the career development skills and capabilities we were trying to build with students.

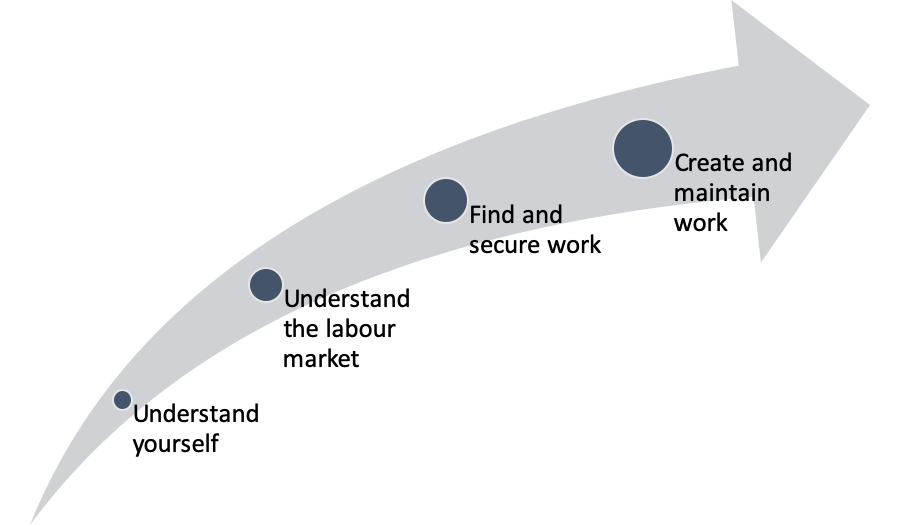

Led by this concept, I developed a capability framework – the career literacy framework (CLF) shown in the image below – based on the Australian Blueprint for Career Development and contextualised to the university environment through incorporating graduate employability research and a thorough audit of our work.

The four core capabilities each capture a range of career development skills with learning outcomes mapped against them. Together, they enable the development of career literacy, which – following established definitions of literacy for various knowledge domains – I defined as the capability to access, critically assess and use career information to successfully manage one’s career over one’s lifetime.

The two main features of the CLF are (1) a building-block type arrangement where capabilities build on one another, and (2) the developmental nature of career literacy, indicated by the upward arrow in the model. We do emphasise in our work that career development is not a unidirectional process that starts with understanding yourself and ends with creating and maintaining work. The circular process of conscious reflection is a critical part of career development (but adding another arrow without overcrowding the image exceeded my graphic design capabilities – I would be most grateful for helpful hints!)

Embedding the CLF into academic courses

The CLF felt like a great step into the right direction and it made sense to students in our 1-1 consultations, but we were still struggling with our overall scale and reach.

We had tried before to include career education into large courses, but the academic curriculum at the ANU is traditionally research-focused and there is not a lot of room to add non-academic content. While pockets of work-integrated learning and industry connections do exist, those courses are often small and our contribution tended to be limited to resume or interview workshops.

Course convenors do want their students to do well and build capabilities that enable them to take their academic skills to a good career, but many are not sure how to teach employability, and their understanding of career development is often limited to their own experiences.

The CLF with its deliberate focus on skills and capability building, proved to be the missing link that opened up that space for us. Its in-built flexibility, inclusion of learning outcomes and self-administered learning assessments allow for an easier integration of our content into existing curricula, but most importantly, the CLF uses terminology that educators are familiar with. We now had a common language to discuss best ways to help students increase their employability, using the academic skills the convenors are familiar with.

We started building relationships with convenors who looked after professional practice courses and similar arrangements. Using short and highly visual presentations that summarised the CLF concept as well as simple ways to integrate the framework into academic courses, we focused on showing how academic learning generates transferable skills, and created a simple traffic-light system to show how students’ career readiness can be assessed, forming the basis of a targeted career education module.

The module is built to be scaled up or down easily depending on space in the curriculum, and makes use of both our in-house resources and a comprehensive careers e-learning platform the team had acquired.

One example of a successful integration which is now in its third round, is a professional practice course in the Bachelor of Health Science, led by a highly committed and enthusiastic convenor who gave us a lot of freedom to bring in our content. One of the most popular resources we developed was a two-step activity using the RIASEC model to firstly link individual preferences to suitable medical careers (CLF capability #1), and then challenge the students to mentally step into careers on their least preferred RIASEC combination and develop strategies to work well in a job that at first sight appears to not be a 100% ideal fit for them (CLF capability #4).

The CLF has since been used to embed career education content in a number of courses across disciplines from health science to applied policy research and social sciences. We have more than quadrupled the number of students reached and are looking to scale up further by creating self-paced, online programs that can be studied in a standalone format or be utilised as pre-course work, with more in-depth tutorials led by our team extending those skills during a course.

I am keen to develop the career literacy concept further, so if you are interested and would like to chat more or just want to send me your thoughts, I’d love to hear from you. [email protected].