Recovering Jobs After the Recession: a Role for Career Guidance

29/07/2021

Dr Peter Davidson is a Principal Advisor at the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS). He is also an Adjunct Senior Lecturer at UNSW Sydney and principal at needtoknow policy consulting. ACOSS is a national advocate for people affected by poverty, disadvantage and inequality, and the peak council for community services nationally.

The deepest recession in a century last year was followed by the fastest jobs recovery in the first six months of this one. What does this mean for people who find themselves unemployed? What role can career guidance play?

In brief:

- There are 1% more jobs than before the recession but that doesn’t mean the labour market is tight – if it was, wages would be growing much faster.

- There are still five unemployed and under-employed people per vacancy, together with a greater number of people seeking to change jobs.

- A sharp recession followed by a quick recovery creates a lot of churn in the labour market – with many unfilled vacancies, even though many people are seeking employment.

- One reason is ‘mismatch’: people can’t just abandon their rental and move to regional Australia to pick crops, and employers are still reluctant to take on people unemployed long-term, older people, or people with disability.

- Most people on Jobseeker Payment have received income support for over a year, and they remain at the end of the queue.

- Career guidance and training have a vital role to play in helping people adjust to these rapid changes in the jobs market, and preparing them for the jobs that are available.

- People who are unemployed or returning to the paid workforce after providing fulltime care need more than a careers website – they need professional career guidance.

- The government has established a plethora of career advice programs for people on income support, but less than one in ten people in relevant target groups have access to them.

- The main employment services program, jobactive, is designed to push people into the first available job, not to offer career advice.

- At $44 a day, unemployment payments make it hard for people to commit to further education and training.

- Benefit rules restrict access to longer courses, and adults in those courses must move to the much lower Austudy or Abstudy payments.

- If we’re serious about lifelong learning, building an agile workforce, and reducing poverty, all this must change.

The overall picture: jobs lost and gained since the recession

I’ll begin with some figures that give a sense of scale of the roller-coaster ride we’ve been through in the labour market.

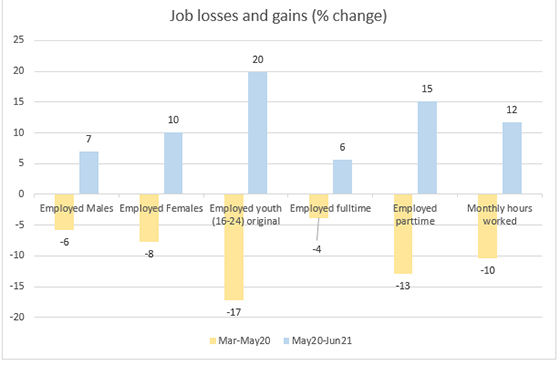

Figure 1 shows the breath-taking scale of job losses in the recession from March to May 2020. Worst affected were young people (17% of their jobs were lost), women (8%) and part-time workers (13%). This was the first recession that disproportionately affected women and part-time jobs, since it was service industries that bore the brunt, including hospitality, tourism and the arts. Casual workers were especially hard hit, with 28% leaving their jobs during the recession.

The impact soon spread to fulltime and male-dominated jobs. As lockdowns were eased later in 2020 (outside Melbourne) there was a rapid recovery in female and part time jobs, followed by a slower recovery in male and fulltime jobs.

By June 2021, there were 1% more jobs than before the recession a year earlier – slower jobs growth than in a ‘normal’ year, but an extraordinary result given the pandemic. The jobs recovery extends across male and female employment, and full and part-time jobs. Overall monthly hours worked recovered more slowly, reflecting the impact of the downturn on part-time working hours.

Of course, the Delta variant and prolonged lockdowns could overturn those gains.

Figure 1

Source: ABS Labour Force data

Source: ABS Labour Force data

How hard is it for people to find employment?

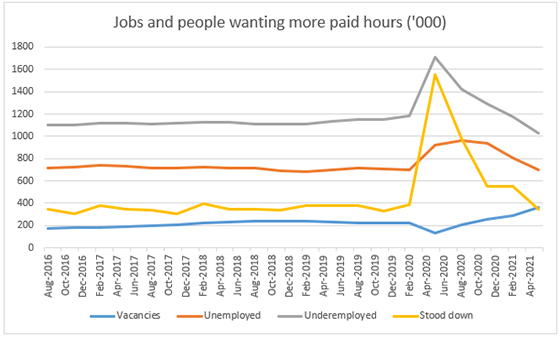

There may be more jobs, but that doesn’t mean it’s easier for everyone to find one. Figure 2 compares trends in unemployment, under-employment and job vacancies. All were fairly stable until the recession. Then, from February to May 2020, unemployment rose by 33%, under-employment rose by 44%, and the number of people employed but stood down (mostly on JobKeeper payment) rose by 300%. If those stood down are included (an ‘adjusted unemployment’ measure used by the Treasury), the unemployment rate rose from 8% to 19%.

Over the same period, job vacancies fell by 43%.

As lockdowns eased and employment recovered, finding a job wasn’t as hard but in May 2021 there were still five unemployed and under-employed workers per vacancy. If we include people changing jobs or entering the labour market, the average number of applicants for each job is much higher.

Figure 2

Source: ABS Labour Force data.

Note: ‘stood down’ includes ‘no work available’ Most of these people were on JobKeeper Payment.

The number of vacancies has reached a long-term high, but it doesn’t follow that the labour market is ‘tight’ and workers can drive a hard bargain for higher pay. Vacancies are high because last year’s massive job losses created more than the usual ‘churn’ in the labour market. A recent British report puts it this way:

"In a fire alarm test, work is switched off as everyone troops out the building and mills around outside. When they head back into the building, you get a queue forming at the entrance. The queue forms despite there being a perfect match between the supply of workers and demand for them (desks), because it takes time to overcome the entrance bottleneck." Understanding the labour market – pandemic not pandemonium, 2021

Bottlenecks are also likely to emerge, and vacancies will take longer to fill, when jobs are suddenly restored after a lockdown. People can’t just abandon their hard-won rental in the city and move to pick fruit or work in hotels in Cairns. Also, many people were understandably reluctant to work in public-facing jobs while the virus was still circulating.

A growing mismatch between jobs and skills

A few years after a recession, the labour market usually settles down and vacancies are filled more quickly, but many people are still left behind. The reasons for this include mismatches between their skills and capacities and those employers want, and also the perception that some people don’t fit the mould of the ‘ideal worker’ (discrimination on the basis of age, colour, or disability).

This mismatch is aggravated by the restructuring of jobs that occurs during recessions and recoveries. The pandemic has lifted the pace of job restructuring. As more people work from home, demand for services in inner cities has fallen. Employers are advancing their plans to invest in new information technology and automation.

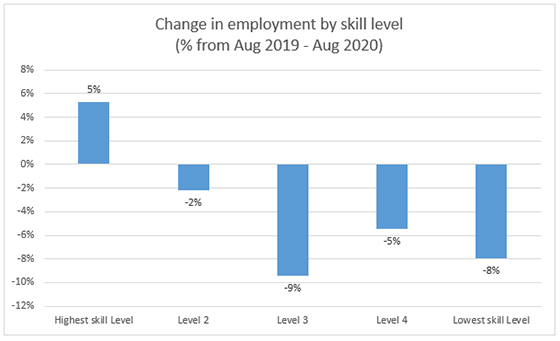

Figure 3 shows that the recession boosted higher-skilled employment at the expense of entry-level jobs. Professional jobs increased over the year to August 2020 while middle-tier and entry level jobs declined. Since last August, it’s likely that many lower-skilled jobs were restored as the impact of lockdowns on service industries such as hospitality eased. However, the shift to higher-skilled jobs is a long-standing trend.

Figure 3

Source: ABS Characteristics of Employment

Note: ANZSCO skill levels.

Those left behind

High unemployment can become self-perpetuating. Once people are out of paid work for a year or more, their skills and confidence wane and employers are reluctant to hire them. Those already unemployed long-term before the downturn find themselves at the end of a longer queue.

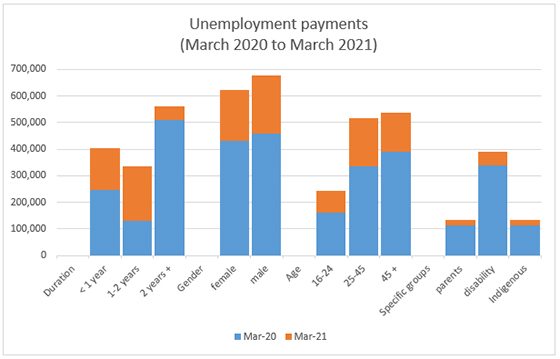

Figure 4 profiles people receiving Jobseeker and Youth Allowance payments before and after the recession.

Before the downturn, of the 886,000 recipients of unemployment payments, three-quarters had received income support for over a year, four in ten were aged 45 years or more, and four in ten had a disability (these groups are not mutually exclusive).

In the recession, the number of people on unemployment payments peaked at around one and a half million. The share of recipients unemployed for less than a year rose sharply from 28% to 57%, while the share of young people on unemployment payments rose from 18% to 31%.

In the recovery, those closer to employment found jobs and the profile of unemployment payments shifted back towards older people, people unemployed long-term and those with disabilities – though the impact on the careers of young people entering the labour market last year will be profound.

In May 2021, there were around 1.2 million people on unemployment payments including about 900,000 on income support for more than a year. Long-term unemployment rises sharply a year after a downturn, but it can take a decade to get back down to the pre-recession level.

Figure 4

Source: Department of Social Services income support data.

Note: The recession commenced in April 2020. The orange bars show the overall increase in recipients from before the downturn (March 2020) to one year later (March 2021).

‘Parents’ refers to principal carers of a child under 16 years.

There are more people on unemployment payments than classified as unemployed by the ABS, since many older recipients and people with disability are temporarily exempted from job search requirements.

Career guidance and training plays a vital role after a recession

Career guidance and training comes into its own when dealing with mismatches in the labour market. People who lose their jobs or enter the labour market after a recession need guidance and support to search for the right jobs, and to re-skill so they have a real chance to secure one.

People who are unemployed usually have lower qualifications: in 2019, 34% had less than Year 12 qualifications compared with 14% of the overall paid workforce.

Yet the prevailing ethos of employment assistance in Australia is ‘work first’. The idea is that people should be pushed to apply for a large number of jobs (currently 20 a month) in the hope that if they pick up entry-level work, they can build their career from there.

One problem with this approach is that these days, most entry-level jobs are part time and casual, so the job might not pay enough to meet basic living costs and it might not last. In 2017, of all hospitality workers 79% were casuals, along with 58% of labourers, 55% of farm workers, 45% of cleaners and 48% of sales assistants. Most jobs obtained by jobactive participants are part-time.

In recent years, the government has recognised that many people searching for employment need career guidance and training. This year’s Federal Budget extended for a year the $500 million Jobtrainer program (matched by State governments). The National Skills Commission and Careers Institute map trends in demand and supply for skills and jobs across the country. That intelligence is used to inform the purchase of Jobtrainer courses, and to inform unemployed people about jobs and courses available to them.

It’s one thing to use sophisticated workforce modelling to inform programs like jobactive and Jobtrainer. As practitioners on the ground know, it’s another thing entirely to connect the right person with the right course and the right employer in the local labour market. The new Local Jobs program - which funds employment facilitators and task forces in each labour market region to better connect employment and training with the needs of employers and unemployed people - should help.

Commonwealth career guidance programs are expanding, but many still miss out

Professional career guidance can also help, whether in an education or employment services setting. A plethora of Commonwealth career support programs are used by people on unemployment payments, including:

Aside from the widely-criticised Parents Next program, the main problem with this complex array of programs is that it reaches only a small fraction of people searching for employment who are likely to need career guidance. Table 1 compares the number of participants in these programs with their potential target groups. Most jobactive participants (of whom there were 1.3 million in December 2020) do not have access to professional career guidance, only low-level help with job search and resumes backed by the information available online via the Careers Institute.

| Program |

Number of Places Filled (2020 or 2021) |

Potential Target Group (December 2020) |

| Transition to Work |

43,000 1. |

237,000 3. |

| Skills for Education and Employment |

14,000 1. |

403,000 4. |

| Career Transition Assistance |

5,000 1. |

349,000 5. |

| Parents Next |

82,000 2. |

470,000 6. |

| Potential Demand in jobactive Caseload |

|

1,327,000 7. |

| Total |

144,000 |

1,797,000 |

Sources: responses to Senate Estimates questions, DSS social security payments statistics (December 2020)

Note: Comparison of participants in various career guidance programs for unemployed people with the number potentially needing such support (noting that not all necessarily do).

1. in January 2021

2. through 2020

3. People under 25 years in jobactive

4. People with CALD backgrounds or lacking Year 10 qualifications in jobactive

5. People 50 years and over in jobactive

6. Principal carers in jobactive and people on Parenting Payment

7. jobactive is not designed as a career guidance program, though many participants (in addition to groups listed above) are likely to need it.

While not everyone searching for employment needs career guidance, it’s very likely that more than one tenth of people on unemployment payments do, given their disadvantaged profile.

The government expanded career support in this year’s Budget, including Transition to Work for young people. The decision to un-cap the Skills for Education and Employment program is welcome, given that 44% of adults lack the literacy skills required in everyday life and that many who have lost jobs recently do not have English as a first language, but there’s a long way to go.

What should happen to career guidance and training for unemployed people?

A new career guidance program should be established to make this essential service available to all people searching for employment who need it. This would have components for the different ‘target groups’ above. It would extend to those who currently miss out, including:

- Parents on income support with school-age children (replacing Parents Next);

- Carers of people with disability returning to the paid workforce;

- Middle-aged unemployed workers who need to reboot their careers.

Unemployment payment rules that restrict participation in further education and training should be eased, including restrictions on full time courses extending beyond 12 months and excessive requirements to apply for jobs while studying. The Austudy and Abstudy payments for adult students should be increased to the same level as the Jobseeker Payment, which should itself be raised from $44 to $65 a day to lift people out of poverty.

ACOSS has developed a suite of proposals to recover jobs after the pandemic. We must ensure that people are not left behind on unemployment payments long-term after the economy recovers. Career guidance and training to help overcome the mismatch between their skills and capacities and those needed by employers in a rapidly changing labour market is a key part of this.